A Scaffolding for Las Palabras Son Muros

Surveying one of Rafael Domenech’s books is like strolling south from the Socrates Sculpture Park, like walking into any urban residual space, at once foreign and prosaic. You meander, confronted with unexpected textures, wrapped objects, partial views (through grates, fences, and other barriers) through incised or translucent papers. Abstraction flows in shadows, close views, and architectural ornamentation. You notice graphics of hand painted auto shop signs, of anonymous graffiti, of the urban planner’s directives, of the artist’s overlaid text. There is a need for re-orientation, which could mean flipping over the book to read in reverse, or looking up above the skyline to see the urban topography. The may encourage an unexpected piedra negra (black rock) equally out of place on the sidewalk or sandwiched between the hard covers of a publication. These residual spaces are telling in both the landscape of the book and Astoria. They are in-between, surplus, and marginal.

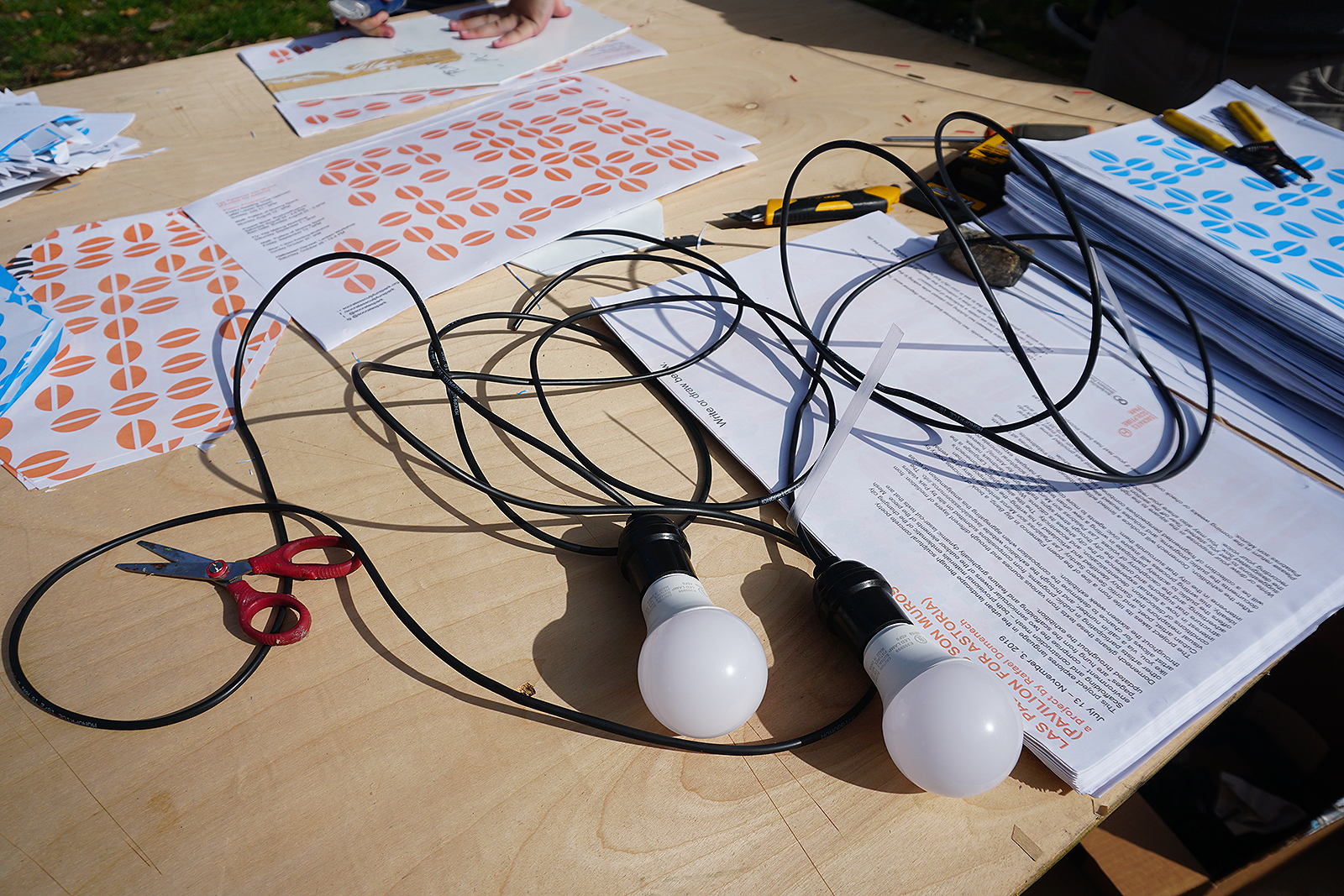

Las Palabras Son Muros [Pavilion for Astoria], an expanded book of sorts, draws on the many threads of Rafael Domenech’s practice from automation to book-making, from psychogeographic wanderings to light-infused installations. Some of its elements are: two scaffolding and construction mesh towers installed at Socrates Sculpture Park for three months, a series of workshops: book-making, kite-making, lantern/lamp making, t-shirt printing; performance and poetry readings; a concrete poetry submissions system, a rotating series of mesh cut texts drawn from the former, and now, in its final iteration a book that documents and reflects on this layered process.

What kind of curatorial text can frame and support a sculptural-light installation-workshop intensive-collaboratively-composed-concrete poetry-architecture-as-book project? Luckily, Domenech has assisted me in the task with his inventive layout. Cut through the middle, the pages flip more easily, separating paragraphs from a chronological flow, fragmenting thoughts, and recombining them: back to front, from the bottom up, and inside out. The feel is not dissimilar from the experience of the work itself.

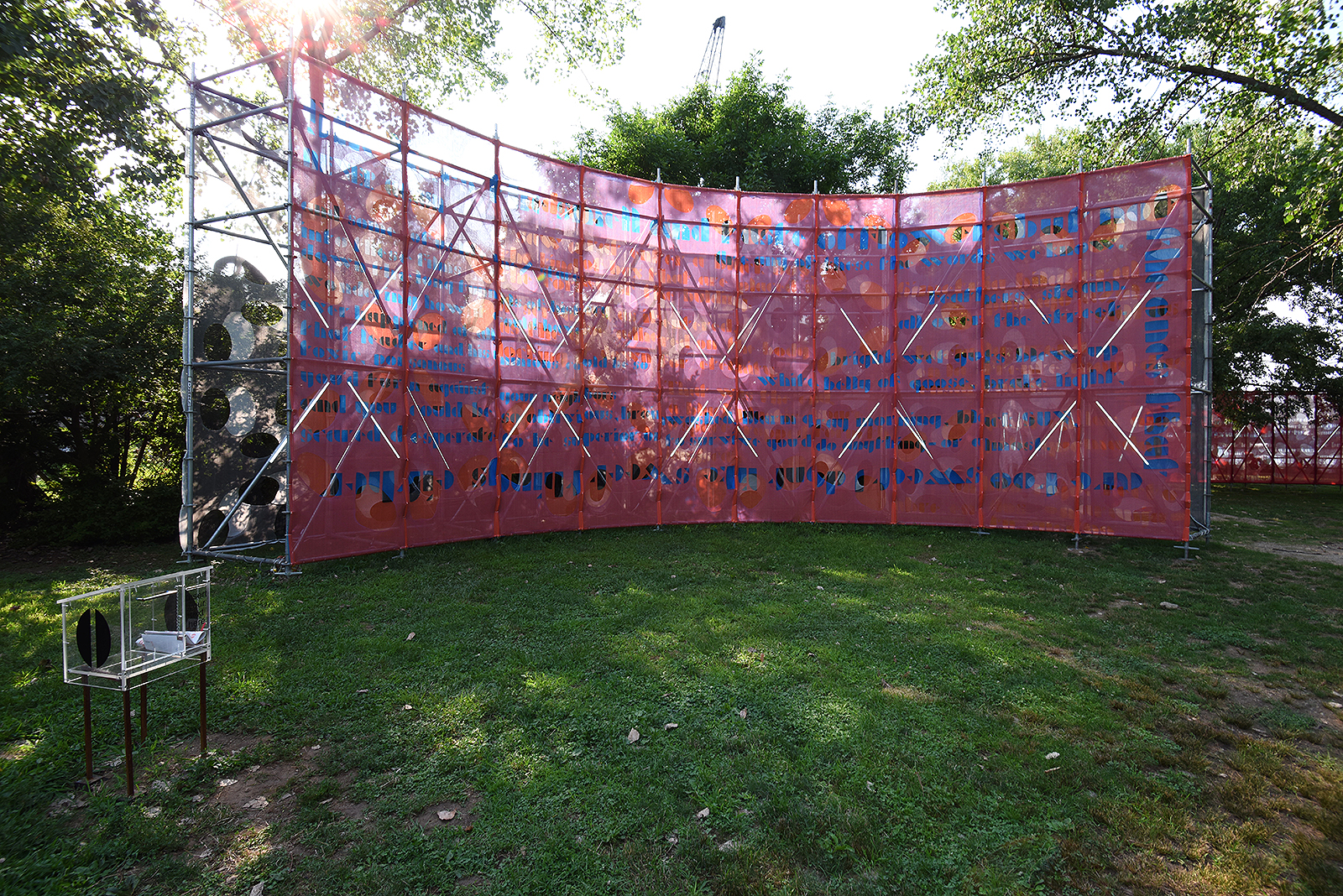

A celebratory opening event on July 13th drew a mix of curious local park goers and art world followers of the project to the two large scale scaffolding arcs bound in bright orange and blue construction mesh. The two towers were at once architectural in their grand shape and experiential in their play with light and color: one spanning 56 feet across and 10 feet high, the other denser and taller at 36 feet wide and 20 feet high. The public was able to enter the corridor made by the scaffolding skeleton and become immersed within its “pages”. The two-color layering of mesh, the LEDs framing the structure’s interior and the shadowplay under the park’s southern canopy concentrated the vibrancy and dynamism of this luminous between-space through which children ran. There was a light breeze in the air. Circulation occured: people, ideas, and printed tabloids.

A Dislocation / An Empty Center

Cuban poet and polymath Severo Sarduy (1937-1993) is one of the many points of departure that lead to Rafael Domenech’s Las Palabras Son Muros, and thus may be considered a three dimensional concrete poetry project. Sarduy, living and working in exile like Domenech, troubled the idea of a national aesthetics, while finding fodder in lived experience in Cuba. But their stronger similarities reside in a dedication to cosmologies and world-ordering, an embrace of both visual and textual fragmentation, and unapologetically ornate and complexly layered practices.

The first lines from Sarduy’s poem Big Bang were among the first texts represented in Las Palabras Son Muros, rendered in one of Josef Albers’ stencil ‘combination fonts’. Albers’ fonts interest Domenech because of their modular logic and because they were specifically created for large scale advertising (on buildings and billboards). Reduced to constitutive units, ten shapes, derived from parts of a circle, triangle and rectangle, comprise all the characters of the font. Laser-cut lettering in mesh exposes the phrase: “Las galaxias parten alejarse unas de otras a velocidades considerables. Las más lejanas huyen con la aceleración de doscientos treinta mil kilometros per segundo, próxima a la de la luz. El universo se hincha. Asistimos al resultados una gigantesca explosión.” In English: “Galaxies move away from one another at considerable velocities. The ones furthest away escape with the acceleration of two hundred thirty thousand kilometers per second, approaching the speed of light. We observe the result of a gigantic explosion.” Rendered in semi-transparent construction mesh, dappled with the light passing through the overhead foliage, the text is not easily legible.

Sarduy begins his book with the contemporary origin story of the universe, stressing this cosmology as guiding force of our thoughts, words, actions and being in the world. The poem easily functions as a map for his theories of the Neo-Baroque episteme, highlighting his interest in the interplay of different signs in a system. The book slips into concrete poetry on certain pages; visioning a sphere by lines of stanzas obliquely knit across the white of the page and re-orienting the viewer on page, in book, in space, on Earth, in this galaxy, in the universe. For Sarduy, the cosmological battle between Galileo’s world ordering of circular planetary orbits and Kepler’s vision of elliptical paths reverberates into cultural production, leaving traces in the hierarchies and tendencies in painting, architecture, and literature of the 17th-century, influencing figures from Pierre de Cortona to Gongora.

Big Bang focuses on contemporary cosmology. In a 1972 interview, Sarduy noted the implications: “The center of the universe is empty; it is a polyvalent and movable center.” Big Bang, as described by Rolando Perez, “affirms by analogy and resists linearity”, following the possibility presented by abstraction and establishing a table of correspondences among various phenomena. Demenech similarly uses abstract systems to frame everything from broad world-views to the mundane consciousness of daily interactions of bodies, from human to celestial. In Las Palabras Son Muros, empty centers abound. It’s geometries invite metaphor: the elliptical cut in the mesh a view to the setting sun, our center of gravity, or the semi-circular arcs of the scaffolding, drawing attention to two separate foci. Viewers attention is divided between the two arced structures which Domenech used as a backdrop to performances, readings and workshops conducted with the space of the curve. This dislocation of is further enhanced in the resulting book-object. Cut holes, half pages, and overlays disrupt smooth consumption of information, yet there are clear sections, titles and texts for interpretive framing, expressing the fundamentally human desire to convey meaning. Is it a document or autonomous art object? Where is the locus (what is the focus/foci) of the work?

Poetry of Recombinations

So ubiquitous in New York City, scaffolding is a reminder that the city is constantly making and remaking itself. Employed for new construction as well as for maintenance of facades of historical buildings, this clever infrastructural system comes and goes. Always temporary, always alongside another more permanent structure, always in service of action and change. They are often perched atop a sidewalk bridge, those tunnel-like structures framed with plywood that guide and protect pedestrians from falling objects, and thus out of sight. Domenech brings these omnipresent, somehow both imposing and invisible, elements down to eye level and into plain view, refocusing attention to the dynamics of the ever-evolving nature of the city.

The modular iterative nature of scaffolding befits Domenech’s working process, which involves recombinations of standard elements. Both the process and materials are elements: cutting holes, layering, illuminating, printing, composing on t-shirts, paper, mesh, and sky. For his workshops, he retro-fitted construction scaffolding lengths, joints and screw jacks into a platform onto which he placed sheets of plywood to make tables for working.

“Words are walls”, the English translation of the title, suggests the importance of language plays in making spatial meaning. Words define space. Words shelter. Words shape the individuals that hear them, read them, speak and write them. The word walls of the city–its traffic signs, advertising, “walk sign is on for all crossings”–all frame our behavior. These words act to organize and divide space, separating the areas that citizens can enter, inhabit, and (pertinent to Socrates) pass time.

In his essay “Semiology and Urbanism”, Roland Barthes, Sarduy’s friend and sometimes collaborator, noted “The city is a discourse, and this discourse is actually a language: the city speaks to its inhabitants, we speak to our city, the city where we are, simply by inhabiting it, by traversing it, by looking at it.” And later concludes: “The city is a poem.” Domenech’s walks remind us that the public can also read the city in this semiotic sense, through spatial signs indicating gathering, crossing paths, surveying, and too often “do not enter”. In our urban experiences we intuit that the inverse phrasing of the title is also true, “walls are words” speaking to city dwellers, the context influencing subjects in tandem with content of the message.

Chief among the reasons that Las Palabras Son Muros feels at home at Socrates is its offer to the public to actively participate in writing a new urban text. The variety of responses garnered from Domenech’s invitation to the public to reflect on the city through concrete poetry, ranging from playful to poetic to stridently activist, indicate the public’s understanding of and interest in language and writing as a means of civic participation. The artist’s prompts were open ended, “Can we create a landscape of permission?” The submissions that the public returned via analog system, returning a hand-written text on a tabloid provided by the artist into a box, were for the most part considered, insightful and keenly aware of the politics of space. One writer focused on the amalgamated sensory experience crossing words into one another: “Chirp, sounds, flower” and “hiss, fuzz, run.” Another expressed alienation and disenfranchisement: “TO WHOM DO THE STREETS BELONG? nOt mE, that’s for sure.” Many focused on the politics of space: “Demolition of an old house undermined the foundations of its neighbors” and “Broken windows policing has poisoned our attitudes to space.”

With all its many events and invitations for public participation Las Palabras Son Muros could easily be labelled as a social practice project, but its approach significantly differs in its centering of linguistic strategies, (verbi-voco-visual) over the quality or texture of the social interaction. Unlike typical socially engaged projects, Domenech did not create scripts, scores or parameters to guide or foster specific types of behavior, but rather let programs function as open proposals to the public. He did not define success by numbers of people engaged, positing art as social service, (although several hundred did actively participate and thousands viewed the work), or by the longevity or effectiveness of the community’s energy or action around considerations of their urban environment, (although the submitted texts indicate the politicized thinking), amounting to art which is in service of social or political change. Significantly, Las Palabras Son Muros unfolded organically in an un-predetermined manner, avoiding regulated participation and imitative behavior, and encouraging emancipated self-directed cultural production.

For Las Palabras Son Muros, these interactions function as scaffolding to the larger decentered project. Like the structures set up to build walls or repair facades, the workshops, walks, readings, and performances provide a temporary support structure to Domenech’s investigation of the city. Each workshop introduced the public to a different aesthetic characteristic deployed in the project: cutting holes, printing layers, graphic identity, book-making, light play, poetry, performance, and pyschogeography. Those who attended workshops would be equipped with new aesthetic tools to employ for their own means.

This scaffolding-like relationship to the public conjures the widely practiced educational theory articulated by Jerome Bruner in the 1950s, in which teachers model and demonstrate problem solving and then step aside, allowing learners to enact on their own, and teachers to offer support when needed. The aim is to produce an emancipated self-directed learner. Likewise, Domenech’s aim is not for the public to be able to re-create their own rote replicas of Las Palabras Son Muros. Rather the public is free to choose which elements to absorb and may recombine (like the pipes and scaffolding), and which pieces they find useful, inspiring, or worthy of their time. These recombinations may manifest as new cultural devices like an inventive mode of language expression (think Albers’s combinatory font or the work of poets Domenech invited to read) or through a more embodied form, such as a new understanding of how to inhabit and traverse through the urban environment. Multivalent and open-ended Domenech’s Pavilion for Astoria is a concrete poem in time and space, in which text, context and substance coalesce.

Jess Wilcox

Curator and Director of Exhibitions

Socrates Sculpture Park